Blog Archives

How ‘The Imitation Game’ Castrates Alan Turing, Again

How do you make a film about the meticulously slow, solitary work of breaking codes entertaining? That’s the question that drags at the heels of The Imitation Game, a biopic of Alan Turing, the man who invented the machine that broke the enigma code, which is largely credited for the victory of the allies over Germany in the Second World War, and was ostensibly the first ever computer. Michael Apted’s 2001 film, Enigma (based on a novel by Robert Harris) attempted (and failed) to do this by turning the story of the Bletchley Park code-breakers into a spy thriller and replacing Turing, an antisocial gay genius, with a dashing heterosexual hero who gets involved in all sorts of contrived wartime intrigue.

The truth is that Turing and his colleagues spent the entire war sequestered from intrigue and violence, painstakingly creating a machine that would break codes used by the Germans to communicate strategies of attack. Once the machine was invented, they all continued to live at Bletchley, determining which attacks to scupper or not, so that the Germans wouldn’t cop on to the fact that their radio communications were being decoded.

The drama in Graham Moore’s screenplay for The Imitation Game is smaller than that of Enigma, focusing at first on conflict between the socially inept Turing (Benedict Cumberbatch) and his debonair competitor at Bletchley, Hugh Alexander (Matthew Goode), and then with his suspicious superior, Commander Denniston (played with a suitably gimlet eye by Charles Dance). Turing wants to build his machine, his nemeses, one after the other, want to stop him. There’s not much else in the way of conflict on show, bar a failed romance with a bright colleague, Joan Clarke (Kiera Knightley) and a particularly muted run-in with the police later in Turing’s life, which is both the horrific heart of this film, and a wasted opportunity.

Turing was prosecuted for homosexuality in 1952, when homosexual acts were still illegal in the UK, and rather than go to prison for two years he accepted chemical castration. This fact is tacked on to the end of the film, which is bookended with a star-crossed teenage romance during Turing’s prep school days, and while the injustice is palpable, the idea of Turing as a persecuted gay man is not. There’s the briefest suggestion that the British government might have had a hand in his demise, but it’s never explored. Rather than even hint at Turing’s adult homosexual relationships, his final scenes involve a deepening of his quasi-heterosexual romance with a simpering (as always) Ciara Knightley, not to mention a fetishised relationship with his machine, which is called Christopher after the object of his childhood affection. There is literally no fleshing out.

Having said all this, the performance at the centre of The Imitation Game makes it soar above the film’s own limitations, self-imposed or not. Benedict Cumberbatch’s deeply expressive face is almost always in close-up throughout the proceedings, and that face embodies a character that you feel for at every turn, even when Morten Tyldum’s direction is clunky, or we’re being fed lots of obvious exposition, or Kiera Knightley is talking through her teeth. Indeed, without Cumberbatch, this film would be nothing worth writing home about.

In the closing credits we learn that Queen Elizabeth II gave Turing a posthumous royal pardon in 2013, which of course was too little too late, given the man’s contribution to winning the war and the millions of lives saved by his machine. It’s also a case of too little to late with this film, which could have really explored the deep injustice meted out against Turing, and what it meant to him as an emotional, sexual adult. As such, while celebrating Turing’s achievements, The Imitation Game castrates him again.

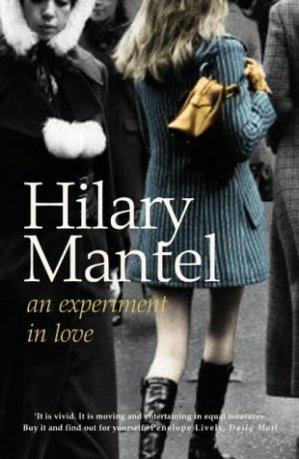

An Experiment in Love

I love when an author hits the big time later in his or her career, like Hillary Mantel, who won the Man Booker in 2009 for Wolf Hall, and who won it again this year for its sequel, Bringing Up The Bodies. Having read both books, and loved them, I started searching Mantel’s back catalogue and came up with a piece of treasure, namely An Experiment In Love.

Set in 1971 its the story of three girls, Carmel, Karina and Juliette who leave their bleak northern town to go to university, and halls of residence, and a whole new world of post-teenage concerns. Beautifully written, with extremely black humor, the book truly comes to sparkling life in the passages about Carmel’s childhood relationship with her angry, dominating mother. They bring to mind Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit, andt the same writer’s recent memoir, Why Be Happy When You Can Be Normal?

Carmel’s bleak outlook on life, underpinned by her dysfunctional relationship with her mother and her childhood friend/nemesis, Karina, is the glue that holds this book together, as the girls face anorexia, unwanted pregnancies, and a shocking denouement none of them could ever have imagined.

If you want a good. absorbing read, look no further.